Data centre growth in the Nordics

Tags

The increased demand for data storage, and predictions of its future growth, is high on the agenda in most Nordic Energy utilities these days. The nature of the business model, where capital intensive infrastructure is deployed is a familiar game for most, and its growing demand for power has a potential impact on the future demand side. So what are the key factors for investors when they’re looking to locate their next data centre, and to what degree do the Nordic countries have a competitive advantage over the rest of the EU? Nordic Utilities need to develop winning strategies to meet those needs and understand how they and their owners can capitalise on the predicted growth.

Across every industry, over the past decade, we’ve witnessed a massive change in terms of digitalisation and adaptation of new technologies. The need for cloud-based solutions has increased exponentially with the increasing use of the ‘as-a- Service’ delivery model for a variety of IT services (SaaS, IaaS, Paas and so on). The emergence of the Internet of Things (IoT) has further boosted the need for storage in the cloud. In other words, there’s a growing need for big data to be stored centrally in a data centre, and users need robust connectivity to enable fast and secure access to their data.

Before exploring the drivers for investing in data centres, it’s useful to understand who the investors are. We have seen massive investments, primarily in UK, Germany and Netherlands, but there’s also been significant growth in the Nordics where approximately 200 data centres have been established over the past decade, with Sweden as a frontrunner.

By the end of 2016, the investments in data centres made by Amazon, Microsoft, IBM, and Google had resulted in these four companies providing half of the available cloud space globally. We can also see that the large IT service providers, such as Evry in Norway and Tieto in Finland, have invested heavily in new data centres to stay relevant for their customers and remain competitive in a Nordic market which has been dominated by large, Indian service providers. Another group of companies that continue to expand their data centre capacity are those who provide data centre colocation. In the Nordics, Basefarm and DigiPlex are examples of colocation providers that offer data storage to multiple customers in modern, high-tech, and energy efficient data centres. In many outsourcing agreements, we see that customers require their IT service providers use a neutral third party for data centre hosting to avoid ‘vendor lock in’.

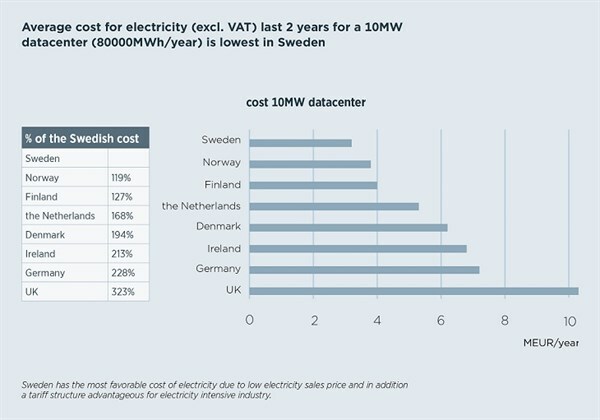

The reason for choosing a location in the Nordics when deciding to invest, is not only to supply data in the region, but also to capitalise on the relatively good connectivity, politically stable environments, natural cooling and the energy mix with a very low carbon footprint. If an average-sized data centre in 2017 is a 10 MW facility, we estimate it can reduce its energy costs by 70 per cent by locating in Sweden compared with the UK, that is before consideration of an energy supply that emits ten times the Nordic energy mix.

Over recent years, we’ve seen several international players setting up in the Nordics. Facebook has recently built its most energy-effective data centre to date in Lulea in Sweden where they benefit from a stable supply of renewables with a reduced need for power back up. Microsoft and Google recently located in Finland, and can capitalise on the link in-between east and west. In Denmark, the data centre industry has seen a higher profile after Apple located a large facility in Viborg. Amazon has announced the establishment of a new data centre in the Stockholm region in 2018, and said the “highly innovative business climate” was one of the main reasons for establishing their first data centre in the Nordics.

The story is somewhat different in Norway. Despite having a robust supply of renewable energy, the country struggles with lower connectivity and less internet traffic in comparison with more progressive neighbouring countries. Norway also has regulations that diverge from those imposed on the EU member countries. This has led to established players having a primary domestic focus and no major international investments are expected anytime soon. That being said, local providers of colocation data centres, such as Green Mountain, have been very successful in getting a solid grip on the sector in Norway. They’ve been particularly successful with clients that require high security in finance, government, health sectors. Several notable domestic initiatives are also underway. Statkraft has defined data centres as a separate business entity and sites have been made available in both Vestfold and Telemark. More dramatically, Kolos is a joint venture set to build the largest data centre the world has seen to date in Ballangen, Northern Norway. In an initial phase, this will consume 70 MW of energy but at a later stage can consume 1,000 MW – 8 twh annually, some five per cent of the Norwegian domestic energy production.

Norway’s safe environment, with natural cooling and affordable renewable energy indicates that the emerging data centre industry will continue to grow. Our analysis suggests that this provides new opportunities for the Nordic utilities and infrastructure funds. The potential demand might also have an impact on future power prices – or at the very least provide a counterbalance to expected overproduction in the future.

Explore more