Inclusive leadership: helping leaders find their VOICE

Leaders need to change old habits. They must adapt how they lead to meet today’s demands. The experiences that shaped their habits when they joined the workforce five, 10 or more years ago are fast becoming outdated as demands grow. Changes in society and markets are forcing them to do more with less, keep BAU operating while planning and delivering strategic change, and lead virtual teams through a once in a life-time pandemic.

At the same time, major trends are fundamentally altering the workplace. Society now expects business to provide social value, not just financial returns to shareholders. #MeToo and the Black Lives Matter movements have highlighted the need to further equality and diversity. And for the first time there are four generations in the workplace, each with their own needs – younger generations expect empowerment, older generations are concerned about learning new skills, for example.

These and other trends put a common demand on all leaders, regardless of industry or organisation – the need to be more inclusive. So, how do you build inclusive leadership?

Leaders must find their VOICE to be more inclusive

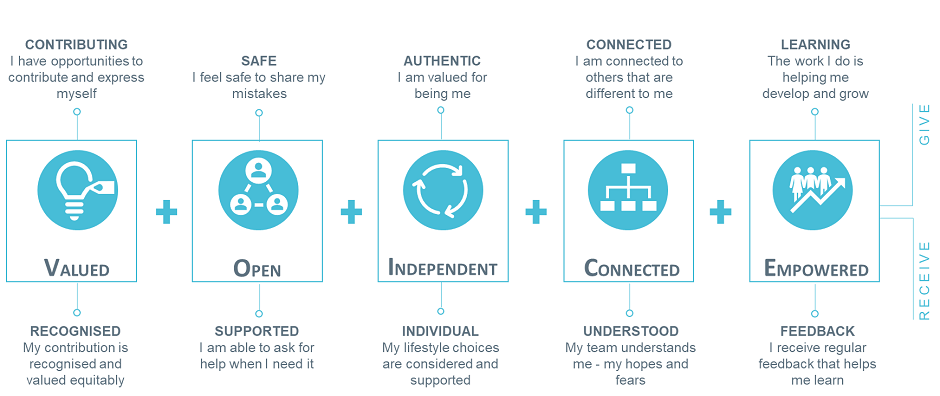

Leaders need to make people feel valued and safe so they can be their authentic selves while connecting to others and continuing to grow. To do this, they should focus on building five dimensions in their teams: Valued, Open, Independent, Connected and Empowered.

We use our VOICE model with clients as it considers two complimentary but contrasting roles people play. Firstly, the ‘giver’ – people give themselves to the organisation and their colleagues. Secondly, the ‘receiver’ – people recognise and use what the organisation offers them:

Valued

Being valued is about more than feeling appreciated. For leaders, it’s about recognising not just the right business results, but the right individual behaviours.

Inclusive leaders pay greater attention to the way their people approach and complete tasks. They also foster self-expression, creating space for people to share their ideas beyond the boundaries of formal role descriptions. The annual task of setting objectives is a great opportunity to promote these behaviours, so people feel valued throughout the year.

One organisation we worked with encouraged its leaders to help their team members develop personal purpose statements. The technique distils an individual’s personal motivations and beliefs into a single statement of intent. Used alongside personal objectives, it can result in more meaningful goals that people are more likely to achieve.

Open

Much has been said about the importance of leaders being comfortable expressing their frailties in building open, psychologically safe environments for their teams. However, leadership disclosure is only a means to an end – the end being the reciprocal disclosure from their people. That, and not a leader’s quest to appear ‘human’, should be the aim.

By normalising ownership of mistakes and expecting everyone at all levels to equally identify and declare their areas for improvement, leaders can allow a meritocratic feedback culture to flourish within the bounds of an otherwise hierarchical team structure.

The Red Arrows, the Royal Air Force’s display team, offer an interesting case study in how to achieve this two-way honesty and use it to drive better performance. A simple example is how the most senior leaders always speak first, sharing their mistakes before getting feedback from their team. Feedback is always two-way, and in the service of the team.

Independent

Independence is a hallmark of inclusive cultures, yet many organisations constrain it. Either they are overly directive in terms of how they define success and the behaviours people need to display, or they put layers of bureaucracy and sign-off in the way of individuals. Either way, the result is that people feel constrained in how they bring their best to bear, or they give up on acting to improve the organisation.

Getting the best from people demands playing to their passions, motivations and strengths. It’s about building the right personal relationships and truly knowing each other. When people bring their full selves to work, they put in more effort and performance improves. There are many ways we’ve seen inclusive leaders achieve this. One way is to find how to link people’s life outside work with work. For instance, at one software company, a leader encouraged a team member to develop an app for supporters of their favourite football club, resulting in the team member being brought onto the pitch and introduced to the team. The result of empowering a team member to bring together work and life passions – positively raising the profile of the company and developing a team member – had a major impact on the whole team and their engagement.

Connected

An organisation is, from one perspective, made up of an arrangement of relationships. Yet many organisations know little about how these connections work in practice, as they focus on formal reporting lines and organisational structures. By understanding the informal relationships, you can see how information and ideas flow. This lack of understanding of network relationships is a problem because inclusive leaders are connectors who look for opportunities to bring others into their network while encouraging diversity and challenge in the company they keep. But without an understanding of how the relationships within an organisation function, this becomes impossible.

To build a complete picture of the relationships between people, we’ve seen one organisation use Organisation Network Analysis to map the formal and informal relationships across a function. This identified the roles their people played within the network, from brokers and SMEs, to highly connected individuals and people who were effectively cut-off. The analysis then helped leaders understand what support they needed to put in place to ‘bring people in’. This is even more important when you consider that networking is one of the key behaviours that enable innovation.

Empowered

Picture a leader who’s with their people every step of the way, showing them how to do things, helping keep them on track. Welcome to the ‘helicopter leader’ – akin to the helicopter parent in their ability to stem the flow of learning. By contrast, inclusive leaders empower their people using the mantra ‘show up, step up, step aside’. Traditionally, leaders are well versed in parts one and two, but struggle to relinquish control for part three.

Surprisingly, leaders can find inspiration for changing their habits in nature. The great northern goose can fly thousands of miles by using a V formation that makes flying 70 per cent more efficient. From a distance, there appears to be a single leader – the bird at the apex of the V. But when the lead bird tires, another goose takes over to give the first a rest. In research on high performing teams, we see different people taking the lead at different points. The formal leader enables this by being willing to fall into line as a team member, rather than getting caught up in hierarchies and ego.

Inclusive leaders can find their voice

Inclusive leaders need to understand what inclusion means from the point of view of their people. It’s a complex picture, but to be effective they need to engage comprehensively. In our experience, the best way to do this is by exploring the give and take of their people across the five dimensions of our VOICE framework.

Explore more