Time to seize the economic potential of the HIP

Tags

In the largest hospital building programme in a generation, the government recently announced an investment of £3.7 billion between now and 2024 for 40 new hospitals. By 2030 the infrastructure investment required could rise to over £14 billion.

This article first appeared in Health Business

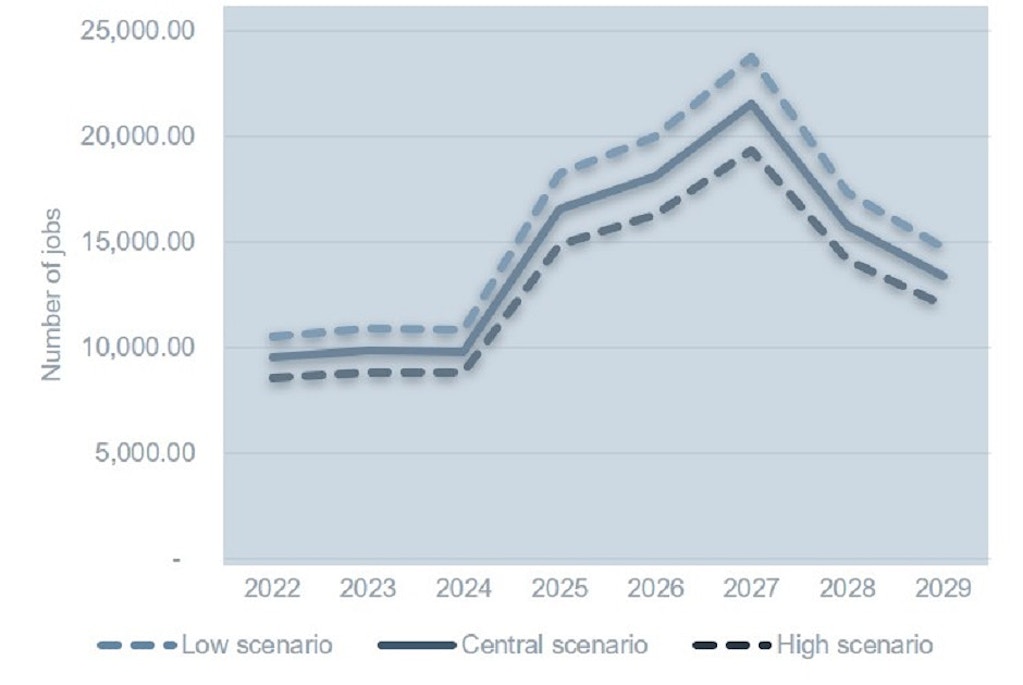

The economic benefits this would generate are huge. PA Consulting’s analysis shows that the construction work alone could create c.13,000-16,000 jobs per year between now and the end of the construction period, generating £7.5 billion in Gross Value Added (GVA) over the 10-year period – two per cent of total UK GVA.

Given the current state of the UK economy and the additional strain the Covid-19 pandemic is placing on the NHS, there is a strong argument for bringing forward the delivery of the schemes in order to significantly reduce the downturn of the economy over the next few years. This would not only be driven by the influx of construction output when building the new hospitals, there are additional opportunities to: level up the economy by building construction components off-site and target areas of low employment; grow technology skills in the workforce due to increased investment in life sciences and Research and Development (R&D); reduce emissions via the modernised hospital estates; and lead to a healthier workforce and further economic productivity, through improved services.

What is the Health Infrastructure Plan?

The Health Infrastructure Plan (HIP) aims to invest in new hospitals, modernise primary care estates, advance new diagnostic technology, improve mental health facilities and help eradicate critical safety issues in the NHS estates. The aim of which is to ensure that NHS hospital estates are equipped to provide world-class healthcare services. Six of the schemes are currently underway and are planned to be delivered in 2025. A further 21 have already been approved to be delivered by 2030. In total, 40 schemes will be invested in, with scope for other hospitals to bid for future funding.

Current state of the economy

The impact of Covid-19 has not only highlighted the necessity of delivering first-class NHS healthcare services, it has had a disastrous effect on the UK economy. From June to August 2020, the number of redundancies grew to its highest level since 2009, with unemployment levels increasing to 4.5 per cent. Construction output has been heavily hit, with the August 2020 level being 10.8 per cent below the February 2020 level. The Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts show that GDP will continue to fall for the rest of the year and unemployment rates could reach the highest level since the 1980s.

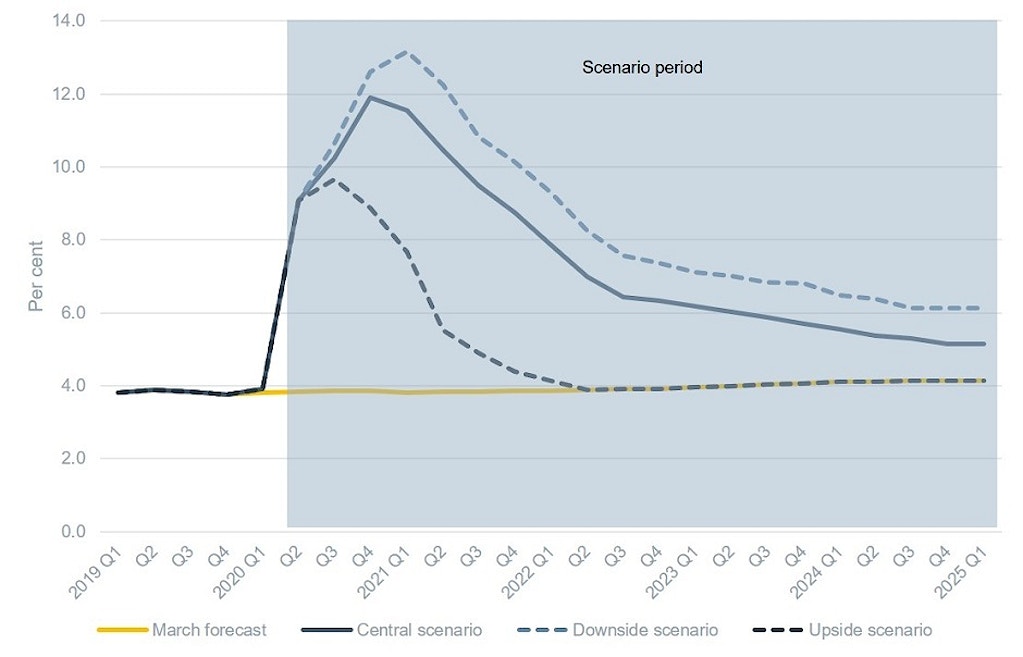

Past experience emphasises that high unemployment tends to persist, with the last two recessions taking seven years to return to pre-recession levels as uncertainty lingers. Furthermore, once people have been unemployed for long periods, statistics show their chances of finding a new job are markedly decreased. Figure 1 illustrates how unemployment is predicted reach its peak at the end of 2020 and going into 2021.

What the HIP schemes mean for the economy

An influx in construction jobs due to the HIP schemes could be just what we need in order to kickstart the economy, especially if we can bring the plans forward to soften the blow of the high unemployment rates and target the downturn at this crucial point in time. The government recently announced that £3.7 billion has been allocated to the HIP schemes over the next four years; a further £11 billion could be needed before 2030 to complete the construction of the hospital projects. As Figure 2 illustrates, if the scheme proceeds as currently planned, only a quarter of the jobs created will be seen before 2025, when the unemployment rate is forecasted to be reaching its highest levels.

Levelling up

One of the arguments against progressing the HIPs is the potential disruption that the construction could cause to an already constrained NHS, particularly at this critical time. However, modern methods mean that much of the construction work can be carried out off-site. This also means that the economic benefits can be targeted in post-industrial areas in greatest need of jobs and investment, especially in areas outside of London. This would have immediate benefit for UK hospitals and create export opportunities for British industry, with potential to distribute built components and construction capability to new hospital developments globally. This aligns with the government’s industrial strategy to put the UK at the forefront of global construction over the coming years.

Off-site construction has been successfully used in other large infrastructure projects. For example, components of Crossrail were manufactured in the West Midlands, and Terminals 2 and 5 at Heathrow Airport dispersed the economic benefits of the construction across the UK, in areas such as Kent, Lancashire, West Sussex and Yorkshire.

Growing our capabilities in life sciences and R&D

The investment in UK life sciences, necessitated by the programme, will also arguably positively impact patient outcomes and our national R&D. The life sciences sector is already a large component of the economy – generating £73 billion of turnover and employing more than 482,000 people. The government plans to harness this by further growing the sector and strengthening its comparative advantage as we leave the European Union.

Furthermore, the investment in R&D by the public sector generates ’spill over’ benefits, stimulating additional investment by private and public sector research institutions. Research has shown that every £1 of public sector funding generates an additional £1.13 - £1.60 private sector funding. Such benefits should not be underestimated.

Environmental impact

The HIP schemes aim to have net zero construction and operational costs, leading to a reduction in carbon emissions within the UK. The hospital site receiving funding had a combined annual emissions output of 300,000 tonnes of C02e in 2018, amounting to a societal value of £4 million. The redevelopments could significantly reduce these emissions using smart infrastructure techniques to reap the environmental benefits throughout the life of the building. For example, 11 office buildings across Manchester and Liverpool are among the first to demonstrate net zero carbon status.

Further uptake of these techniques will go a long way in addressing the property sector’s part to play in the government’s ambition to become carbon neutral by 2050.

Healthier workforce

The investment in life sciences and improvements to NHS facilities and services will also lead to a healthier workforce, reducing sickness leave and improving UK output. The ONS estimates that 141.4 million working days were lost due to sickness or injury in 2018. This is not helped by estimates showing that the prevalence of long-term health conditions is on the rise, which make up 70 per cent of all inpatient days. This is predominantly true of areas of deprivation, which will be hardest hit by the economic recession. It is therefore more important than ever to provide the working population with the healthcare services they need to ensure a productive workforce.

Covid-19 has put great strain on both our healthcare system and our economy. An investment in 40 new hospitals could lead to significant improvements in NHS services and create a flood of construction jobs to stimulate output when we need it most. Targeted off-site construction could further combat output in areas hardest hit by the crash. However, delaying the plans to a point where unemployment and output figures are beginning to recover is likely to mean that we see a reduction in economic returns to the healthcare investment. To have the greatest impact on reducing the economic consequences of Covid-19, an injection of capital is needed as soon as possible. The HIP schemes have the platform to provide this, if we act quickly.

Explore more