Street wise

This article was first published in New Design

PA Consulting (PA) has unveiled its design for a British electric vehicle street based chargepoint. New Design spoke to design and innovation expert, Dan Toon, about the background to the project and a wider look at PA’s design processes and best practice design principles.

Being briefed to create a British design that has the potential to be as iconic as the red postbox or black cab is understandably daunting. It’s no mean feat to design something that could become an icon in the eyes of the public.

Being briefed to create a British design that has the potential to be as iconic as the red postbox or black cab is understandably daunting. It’s no mean feat to design something that could become an icon in the eyes of the public.

The design in question is the recently launched EV chargepoint concept, which was unveiled by the Department of Transport at COP 26. In a bid to show its commitment to achieving Net Zero, the aim is to have these instantly recognisable chargepoints featured across the country to help encourage the adoption of EVs.

“We often think of something achieving iconic status after a certain test of time. So, more than anything, the brief certainly raised the bar in terms of the ultimate objective,” says Dan Toon, design and innovation expert at PA Consulting.

PA believes it was well placed to take on this brief being able to pull a team together that can offer a range of expertise and capabilities all under one roof from user research and product design through to technical engineering and manufacturing. While some of its team operates out of studios located throughout Europe and the US, there is a strong presence at its Global Innovation and Technology Centre in Cambridge, UK. Here more than 300 strategists, innovators, designers, consultants, digital experts, scientists, engineers and technologists work together to turn ingenious ideas into physical and digital reality.

“PA offers end-to-end innovation with design totally integrated throughout. I joke that our designers peer over the shoulders of our scientists and engineers but it is about that genuine ability of design to bring meaning to science, technology and engineering. I think that is something that is quite unique and certainly differentiates us,” says Toon.

“PA offers end-to-end innovation with design totally integrated throughout. I joke that our designers peer over the shoulders of our scientists and engineers but it is about that genuine ability of design to bring meaning to science, technology and engineering. I think that is something that is quite unique and certainly differentiates us,” says Toon.

Together with this in-house expertise, PA also brought its vast experience to the table. Its end-to-end innovation process, which takes ideas from concept, through design, development, and to commercial success, has been used on a wide range of projects for clients across diverse industries.

Arguably one of its most complex innovation projects, according to Toon, was the UK Ventilator Challenge. With the coronavirus pandemic escalating and the country running out of ventilators, the UK government asked PA to help produce 30,000 ventilators in just eight weeks.

“We assessed more than 200 different designs from mature ventilators and working prototypes through to scribbles on scraps of paper. Our interdisciplinary team shortlisted the 15 most promising designs and set up a manufacturing program to get each of them to market within those eight weeks”, explains Toon.

While PA offers complete end-to-end innovation, the client may only need help with a certain part of that innovation process. A project where it was involved much more at the front-end was for a young cosmetics business called Guide Beauty that is on a mission to improve makeup application for all users.

“This was very much an inclusive design project and our involvement was really about focussing on the front-end of the process and understanding the user experience. Our findings were then incorporated into the makeup applicator tools that would really perform as an extension of the user’s hand. Guide Beauty went on to win an iF DESIGN AWARD for this work in the User Experience category,” describes Toon.

“This was very much an inclusive design project and our involvement was really about focussing on the front-end of the process and understanding the user experience. Our findings were then incorporated into the makeup applicator tools that would really perform as an extension of the user’s hand. Guide Beauty went on to win an iF DESIGN AWARD for this work in the User Experience category,” describes Toon.

Whereas with this project the focus was at the front end, for other clients the focus may be much more on the manufacturing side. For instance, Swedish R&D & IP business PulPac have invented a production method that produces a sustainable paper pulp alternative to plastic packaging.

“PA’s role as PulPac’s development partner is working with them to develop paper pulp alternatives in many different markets. This involves offering a range of services from business case development and product design through to the production of machines that will manufacture those alternatives at scale,” says Toon.

“PA’s role as PulPac’s development partner is working with them to develop paper pulp alternatives in many different markets. This involves offering a range of services from business case development and product design through to the production of machines that will manufacture those alternatives at scale,” says Toon.

So when the charge point brief came in Toon felt that it was a fantastic opportunity for PA and they were well placed to take it on.

A multidisciplinary team was assembled to focus their expertise on the complex challenges of this project. One of the key challenges was to create a design that could inspire and accelerate behaviour change. In other words, with this design the government wanted to shift people’s perceptions of electric vehicles so more of them would choose to drive them.

“We know that there are many reasons why existing charging infrastructure is a barrier to people today, such as access, cost, usability and functionality. So our task was to produce an inclusive design that fundamentally enables behavioural change,” says Toon.

“We know that there are many reasons why existing charging infrastructure is a barrier to people today, such as access, cost, usability and functionality. So our task was to produce an inclusive design that fundamentally enables behavioural change,” says Toon.

Focussing on human-centric design principles, gathering insights from users was a crucial first step in the innovation process. Although time was tight, PA undertook thorough user research. It gathered insights from electric car users, traditional motorists, disability and consumer groups and industry stakeholders to draw out the real needs of people and businesses. This work complemented the government’s consumer experience consultation and ensured the design was aligned with accessibility standards, infrastructure strategy and local authority guidance.

“This enabled us to really get to grips with what the current challenges and frustrations with charge points today are. We also then did a technology landscaping piece of work to help us understand where technology is today and how it’s likely to evolve. This all fed into our design,” says Toon.

“This enabled us to really get to grips with what the current challenges and frustrations with charge points today are. We also then did a technology landscaping piece of work to help us understand where technology is today and how it’s likely to evolve. This all fed into our design,” says Toon.

As this design had to have the potential to become iconic, to help it decode what iconic Britishness is, PA also enlisted the help of a semiotician who brought specialist expertise in semiotics – the study of signs and symbols. “Through looking at British design over the years and how it’s evolved we then distilled that into ten antagonisms. This series of antagonisms would be used as inspiration for our expressive design process,” says Toon.

“For instance, one antagonism was ‘heritage breakage’. This is about how British iconic design has over the years done an excellent job of celebrating our heritage, but at the same time breaking it enough to have a new and interesting iconic British design. Another one that helped inform our design was ‘present but unobtrusive’, which sounds strange but it’s very applicable to this project,” he adds.

“And the fundamental antagonism we had to manage was between getting the functionality of the design exactly right and the need to sprinkle a bit of joy so that it would raise a smile when people used the charger or saw it at the end of their street.”

PA also collaborated with service design experts at the Royal College of Art (RCA). It was critical that the design delivered a seamless service. With the help of the RCA’s experienced designers and recent graduates, they could together ensure a design was created that could be both iconic and meet the needs of a myriad of stakeholders.

All this insight and research fed into the design process and a set of best practice design principles spanning five characteristics was established. These included functionality, accessibility, sustainability, affordability and adaptability. Through a series of design sprints, PA then produced concepts of the four most promising designs.

All this insight and research fed into the design process and a set of best practice design principles spanning five characteristics was established. These included functionality, accessibility, sustainability, affordability and adaptability. Through a series of design sprints, PA then produced concepts of the four most promising designs.

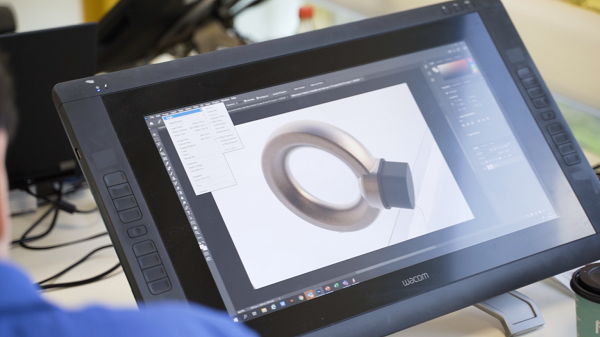

From sketches they very quickly got physical with these concepts and produced models in its in-house labs. These were then shown to different members of the public during face-to-face focus groups at its Global Innovation and Technology Centre in Cambridge. Here these users had the opportunity to try out the prototypes and vote for their preferred option.

From this feedback, the design team carried out further iterations on the four concepts. These were then presented to experts and key stakeholders. Following rigorous discussions, one design emerged as the most desirable to take forward. A full-sized prototype of this concept vision and accompanying set of design principles were created. This went to COP26 where it was officially launched.

This final chargepoint design features an instantly recognisable circular handle with materials, size and colour that help blend it into the UK’s diverse surroundings, whilst remaining visible for EV drivers. From PA’s perspective, its simple yet modern appearance incorporates a sense of joy that will hopefully encourage engagement and inspire users to reach out and use the device.

The plan, according to the Department of Transport, is to roll these out across the country from 2022. Will this chargepoint become as iconic and as recognisable as the red postbox? Only time will tell.

Explore more