The pathway for the hydrogen economy

Tags

This article was first published in Utility Week

With the UK government unveiling consultation papers on its Hydrogen Strategy, industry and the Department for Business, Energy and Industry Strategy (BEIS) must now work together to realise the government’s blueprint for reaching Net Zero.

At the core of this will be defining how policy can support innovation and increase the demand at scale, thereby improving the economics of hydrogen, especially for green hydrogen.

The pathway for the hydrogen economy

The energy markets are changing. As we forge a path towards Net Zero, everything that can be electrified, will be electrified. However, that will not be enough, and this is where hydrogen will play its part.

As part of this role, one of the first significant steps, due to the current economics of hydrogen, will be a move away from a centralised hydrocarbon system. Instead, the market will evolve into fragmented and localised clusters and hubs, where hydrogen will have multiple applications, ranging from the chemical industry and heavy manufacturing, to transport and, on a limited basis, to heat.

This is the central tenet to the government’s decarbonisation strategy of the country’s main industrial areas including Grangemouth, Humberside, Merseyside, Southampton, South Wales and Teesside, where mainly blue hydrogen will be deployed, using attendant carbon capture, usage and storage (CCUS).

Figure 1 shows the UK’s six main industrial clusters, and the government aims to have two clusters to be in operation by the mid-late 2020s and a further two clusters by 2030, with the initial target of capturing 10mtCO2pa.

Fig. 1: Map of UK’s Main Industrial Clusters

The next step will be the deployment of green hydrogen, again in clusters and hubs. This should be facilitated, especially by the government’s initiative to create Freeports, in England and Wales, and Green Ports in Scotland.

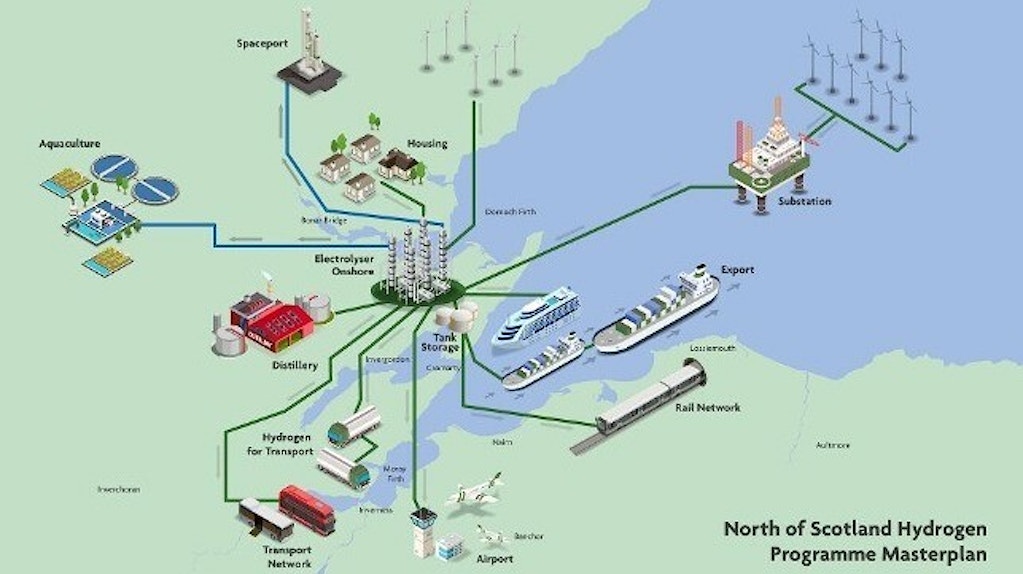

An example is the planned hub at the ‘Green Port of Cromarty Firth’ in Scotland (see Fig. 2). The electrolyser is to be located in the Cromarty Firth and is likely to be powered by on and offshore windfarms, with the main source of offtake being the local whisky distilleries. This will in turn allow them to decarbonise their heating and maltings.

Fig. 2: Schematic for the proposed Green Hydrogen Hub at the Port of Cromarty Firth

To maximise the economics, additional offtake of the hydrogen in these hubs will be in the production of, for example, green steel/cement and waste-water treatment.

In terms of transport, the maritime sector should be a major source of demand, especially as domestic shipping, with attendant tugs and pilot boats, is four times more polluting than domestic aviation. HGV road and rail transport should also be a source of demand and, in due course, domestic aviation should follow suit.

There should be applications for heat. However, given the prohibitive cost of repurposing networks, initially this will be limited to closed-looped networks, ideally with a single point of blending. Such a scheme is already operational at Keele University.

Role of government subsidy schemes

Government funding for such schemes is already underway, with capex grants from the Net Zero Hydrogen Fund.

It is expected that the mainstay of support from BEIS will come in the form of a Contract for Difference (CfD) type mechanism, which will be tweaked for retro-fit/new build and separately negotiated for different use cases including, for example, heavy manufacturing and power generation. Such an instrument will give developers a guaranteed price for the hydrogen produced, thereby allowing them to finance their projects.

The success of the CfD mechanism is illustrated by the UK being the world leader in offshore wind, with a capacity of over 10GW. It allowed the deployment of offshore wind at scale, thereby increasingly de-risking the technology, which brought down the CfD auction strike price by 63 per cent, from £114.39/MWh in 2015 to £39.65/MWh in 2019.

While it is unlikely that this will be replicated at such a pace for hydrogen, the initial deployment of blue hydrogen at an industrial scale should allow for meaningful cost reductions, driven by increased volume and market certainty. This will also help incentivise further pull of the demand from the various hydrogen markets.

This should then be applicable to the deployment of green hydrogen. However, the ingenuity of this strategy is that it will allow for the transition from blue to green hydrogen, as the UK builds on its expertise and quadruples its offshore wind capacity to 40GW by 2030.

The ramping up in offshore wind should lead to a continued fall in the levelised cost of electricity. This will also help to reduce the overall barrier of the economics of green hydrogen, especially where production begins to be deployed at scale within these hubs, with multiple applications.

Then, once green hydrogen passes its cost tipping point, it will likely play an increasingly intrinsic part in the UK meeting its legally binding commitment to becoming Net Zero emissions by 2050.

Explore more